An example of revolutionary defiance and militancy

By Carlos “Carlito” Rovira

On October 15, 1966, the Black Panther Party was born. It is one of the highlights in the history of the U.S. revolutionary movement, and the Black liberation struggle in particular.

Young African Americans dared to stand up and challenge the reins of the capitalist state, to the point of arming themselves to demand an end to Black oppression. Their vision of Black emancipation evolved into a vision of the liberation of all oppressed people and the smashing of the capitalist system.

The U.S. government, terrified by the potential for revolution and the influence these Black leaders and freedom fighters were gaining, resorted to the most extreme violence to destroy the BPP. It is a campaign that is still felt today.

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, as the party was first called, was formed in Oakland, Calif., by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale. The name—and the famous panther logo—came from the Lowndes Country Freedom Organization in Alabama, that which organized for independent Black political action with the help of Stokely Carmichael and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

The formation of the Black Panther Party was the culmination of a resistance over a long history that characterizes the oppression of African Americans in the United States, from the lashes of slavery to the beatings and murders by the police in modern times.

The BPP grew up in the aftermath of the 1965 assassination of Malcolm X — a powerful voice for militant Black self-determination and liberation. It drew inspiration from the Deacons for Defense and Justice, organized for African American self-defense against racist Klan and police terror in the South.

The Panthers recognized the need for an organization that was capable of addressing the racist violence that the Black masses faced. Every gain made by the Civil Rights movement was being matched by violence and lynching by racist cops and the Ku Klux Klan, in the North and South alike.

The Right to Armed Self-Defense

The Panthers won respect and admiration for their militancy and defiance in the face of the racist police state. For example, less than a year after their founding, on May 2, 1967, a group of 30 Black Panthers walked into the California state capitol building armed with shotguns and automatic rifles. The armed but peaceful demonstration was to protest the Mulford Act, aimed at prohibiting citizens from carrying firearms on their persons or in their vehicles.

As the Panthers walked towards the entrance of the capitol building, they were approached by television and other news media. They used the occasion to call upon African Americans everywhere to arm themselves against the systematic brutality and terror practiced by the power structure.

But the party’s efforts went far beyond their call for armed self-defense and their patrols of racist cops. They also carried out consistent community work, gaining the confidence of the people not only in the Black community but among other oppressed nationalities as well.

Panther chapters sprung up in the African American communities of major cities from coast to coast. Wherever they established branches, they tried to set up outreach programs like free breakfast for children and free clothing drives. They used every one of these opportunities to expose the avaricious nature of the rich and powerful who exist at the expense of the poor.

The Panthers were influenced by Malcolm X’s rejection of “turn the other cheek” pacifism for the Black liberation struggle, as well as by the socialist movement in the United States and around the world. Their “Black Power” salute combined with street corner sales of Mao Zedong’s “Little Red Books” of quotations.

The international situation during this period also contributed to the birth of the Panthers. The 1949 Chinese Revolution, the 1959 Cuban Revolution, the Vietnamese Revolution and the heroic struggle of south Vietnam’s National Liberation Front against U.S. imperialism, along with the other national liberation struggles in Africa, Latin America and Asia had a great impact in inspiring revolutionaries in the United States, including the Black Panthers.

Their militancy and revolutionary politics quickly put them in the center of the African American liberation struggle, as well as in the growing mass movements that were sweeping the country.

Capitalism is the Problem

More and more, the party put the blame for the plight of the African American people on the capitalist system. It rejected the view that the problems of racism could be solved within the confines of the exploitative system, or that it was possible to accumulate enough capital in the Black community to rival capitalism with “Black capital.” Instead, Panther speakers called for socialist revolution within the context of the Civil Rights era.

Their uncompromisingly revolutionary and anti-capitalist stance was the most prominent in what became a new trend within the Black liberation struggle of the 1950s and 1960s.

As part of the political training of its membership, the BPP studied Marxist literature like the Communist Manifesto and the writings of Mao Zedong.

The Black Panther Party was a disciplined and organized revolutionary political entity. The Panthers put forward the need for professional, organizational sophistication in building a revolutionary political party.

While the party’s Ten-Point Program reflected its political views and line of march, it was the membership rules that ensured the internal discipline of the organization. Membership rules touched a range of matters, including mandatory collective study of revolutionary theory; respect for women inside and outside the BPP; and respect for the property of the poor.

Revolutionary Multinational Alliances

The Panthers advocated a united front of revolutionary organizations to guarantee the success of a struggle in the United States. Their organizing efforts extended to Puerto Ricans, Chicanos, Asians, other nationally oppressed people, and the white working class.

They forged alliances of various kinds, such as with the American Indian Movement as well as Cesar Chavez and the farm workers’ movement. The Panthers stood in solidarity with the struggle for women’s equality, especially supporting those sectors of the women’s movement that were anti-imperialist and anti-racist. To the surprise of many, on the heels of the Stonewall rebellion, Panther leader Huey P. Newton publicly supported the struggle to end LGBTQ oppression.

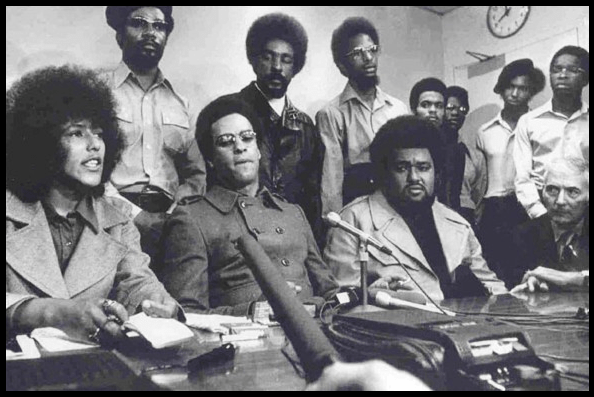

The Panthers perspective was toward building a multinational alliance. Their most notable effort was the Rainbow Coalition, organized in June 1969 in Chicago by Panther leader Fred Hampton, which consisted of the Black Panther Party; the Young Lords, a U.S. organization of Puerto Rican revolutionary youth; and organizations representing Chicanos, Asians, and poor whites. Hampton’s vision was to eventually merge these allied organizations into a single entity, to forge a revolutionary organization with representation from the full spectrum of the working class.

Wherever their agitation work was conducted, on the streets, on campuses, or at public events, the Panthers upheld the principle of solidarity with the liberation movements in the oppressed and colonized countries. At the height of the Vietnam War, the Black Panther leadership made an open gesture of internationalism by offering to send party members to fight alongside the National Liberation Front in their struggle against U.S imperialism.

Fierce U.S. Repression

Faced with the Black Panther Party’s tremendous growth and revolutionary orientation, the U.S. government struck back. It organized a massive political-military campaign, involving the FBI and police departments around the country, to destroy the Panthers’ leadership.

In a now-well-documented campaign called “Operation: COINTELPRO,” the FBI orchestrated covert operations—personally overseen by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover—to provoke conflicts between Black Panthers and other organizations. They employed a network of infiltrators and provocateurs to disrupt the party’s discipline and leadership.

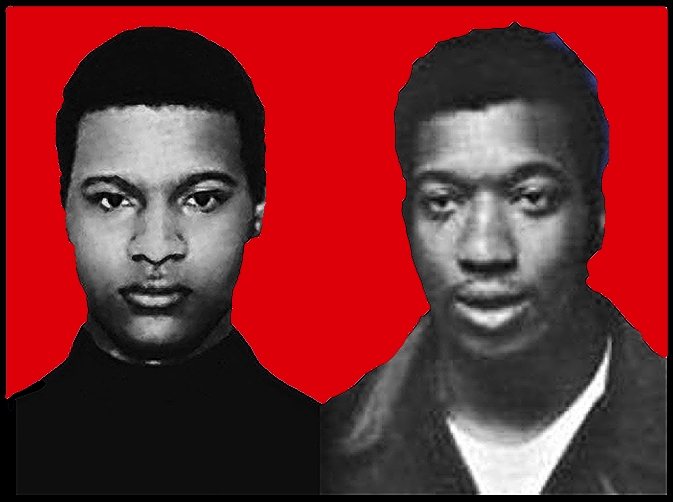

Police attacks were common. Cops routinely raided party offices and the homes of Panther members. Dozens of Panthers were killed outright, often in cold blood. The most notable of these cop assassinations was the December 4, 1969, murder of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in Chicago while they slept. Hampton was 21 and Clark was 22 years old.

Dozens more Panther members and leaders spent years in prison. The campaign to jail Panther leaders and activists long outlived the organization itself. Mumia Abu-Jamal, who at 16- years -old had been the Minister of Information in the party’s Philadelphia branch, was framed up and sentenced to death in 1981. He has been in prison ever since despite a worldwide effort calling for his release.

The Black Panther Party ultimately could not withstand the government onslaught. The combined police attacks and covert operations compounded internal differences. Unable to withstand the tremendous repression, by the mid-1970s the Black Panther Party was essentially defunct.

Lessons for today

Bourgeois historians often try to downplay the role of the state in the destruction of the Panthers. At best, they point to the Panthers as a lesson to revolutionaries, especially from the oppressed nationalities: “Do not dare to struggle, you cannot stand up to the power of the capitalist state.”

However, the rulers were not then and are not now invincible. The fact that the U.S. government relentlessly attacked the Panthers before they had a chance to steel the discipline of their rank & file only points to the need for a disciplined organization of professional revolutionaries today.

As long as capitalist oppression exists, the rise of movements, like the one that gave rise to the Black Panther Party, is a historical inevitability. The Panthers showed that revolutionary ideology and organization, embraced by the most oppressed sectors of the working class, is what the ruling class fears the most.

Everything they did and sacrificed will not be in vain. Eventually, those who aim in the sincerest sense, for socialism, Black emancipation and the liberation of all oppressed people in the United States must strive to embrace and emulate the revolutionary spirit of the Black Panther Party.

LONG LIVE THE LEGACY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY!