For English version https://carlitoboricua.blog/2016/02/07/the-impact-of-the-black-struggle-on-puerto-rican-immigrants-2/

Por Carlos “Carlito” Rovira

La opresión racista da lugar a la solidaridad

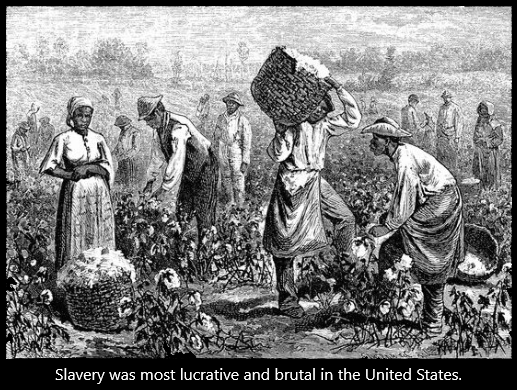

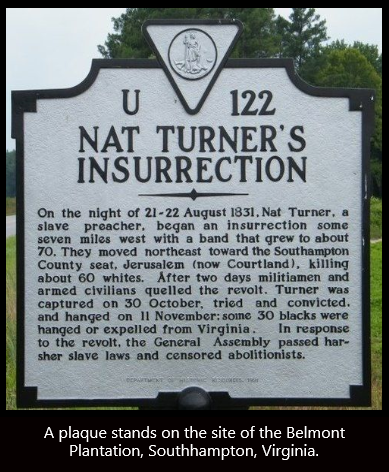

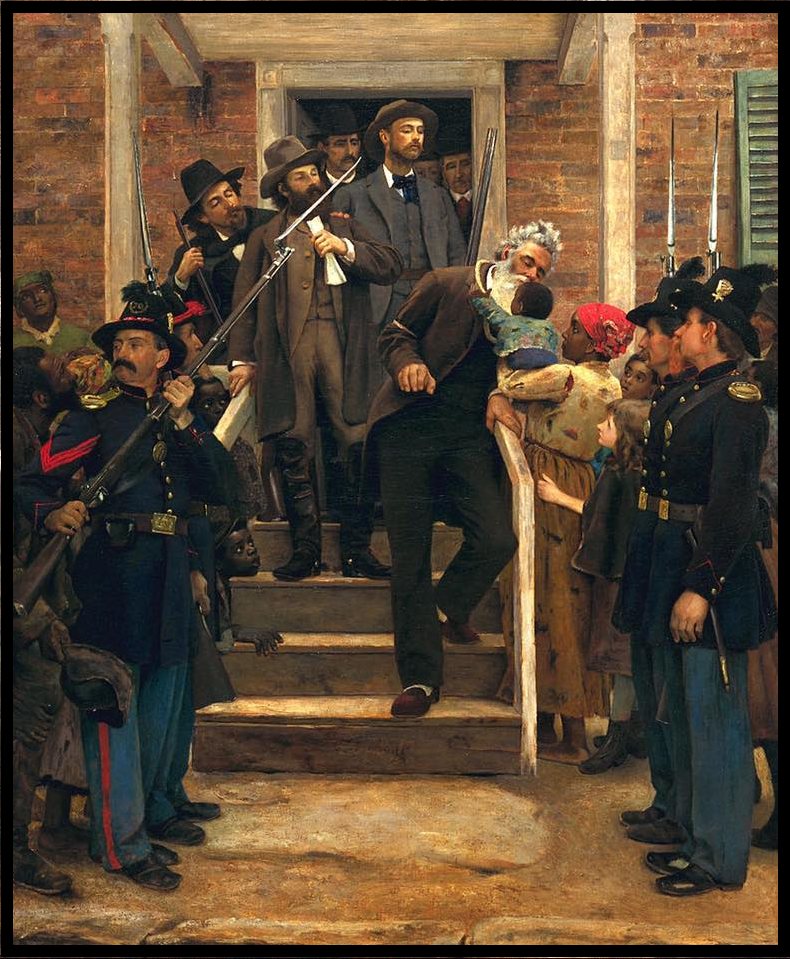

La lucha histórica del pueblo afroamericano fue la consecuencia inevitable de la introducción de la esclavitud por parte de los capitalistas en el hemisferio occidental. La experiencia colectiva del pueblo afroamericano a lo largo de muchas generaciones fue paralela al desarrollo del capitalismo estadounidense en cada etapa. Su difícil situación, desde la era de la trata de esclavos hasta la actualidad, revela la opresión inherente dentro del capitalismo.

El terror racista, la degradación y la discriminación fueron las circunstancias objetivas que impulsaron la existencia de la tradición militante de resistencia en las masas afroamericanas. Su firmeza en muchos momentos clave de la historia resultó ejemplar para el movimiento de la clase trabajadora estadounidense y, en particular, para otras nacionalidades oprimidas. La historia afroamericana está repleta de demostraciones de solidaridad genuina con otras luchas de liberación.

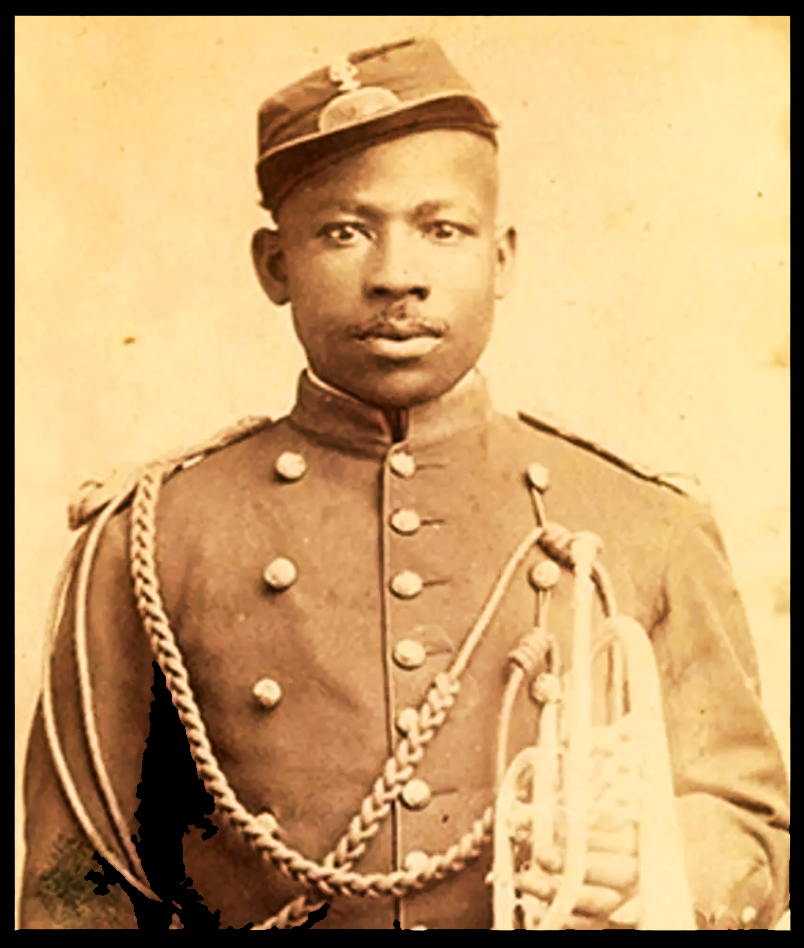

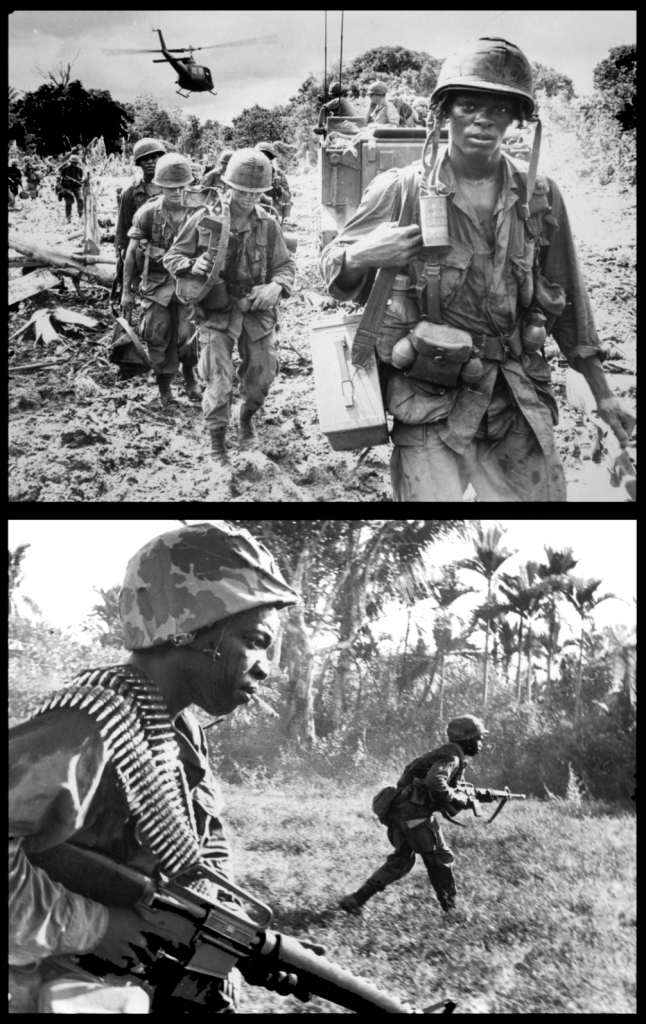

La Guerra Hispanoamericana tuvo un impacto significativo en los afroamericanos, especialmente en los soldados negros que fueron enviados a librar una guerra colonial en nombre del imperialismo estadounidense. Las tropas negras estaban resentidas porque sus oficiales blancos usaban insultos raciales contra los filipinos, que recordaban su propia experiencia en los Estados Unidos. Muchos soldados negros desertaron para unirse al ejército guerrillero filipino anticolonial. El más notable de ellos fue David Fagan, de la 24ª División de Infantería. Fagan se ganó la admiración y el respeto del pueblo filipino y fue nombrado comandante de su ejército guerrillero.

La prensa negra, la Iglesia negra y figuras afroamericanas francas como W.E.B. DuBois, condenaron abiertamente los motivos detrás de la Guerra Hispanoamericana de 1898. El gobierno de los EE. UU., y las gigantescas empresas bancarias buscaron un conflicto militar con España para obtener el control colonial de Guam, Filipinas, Cuba y Puerto Rico.

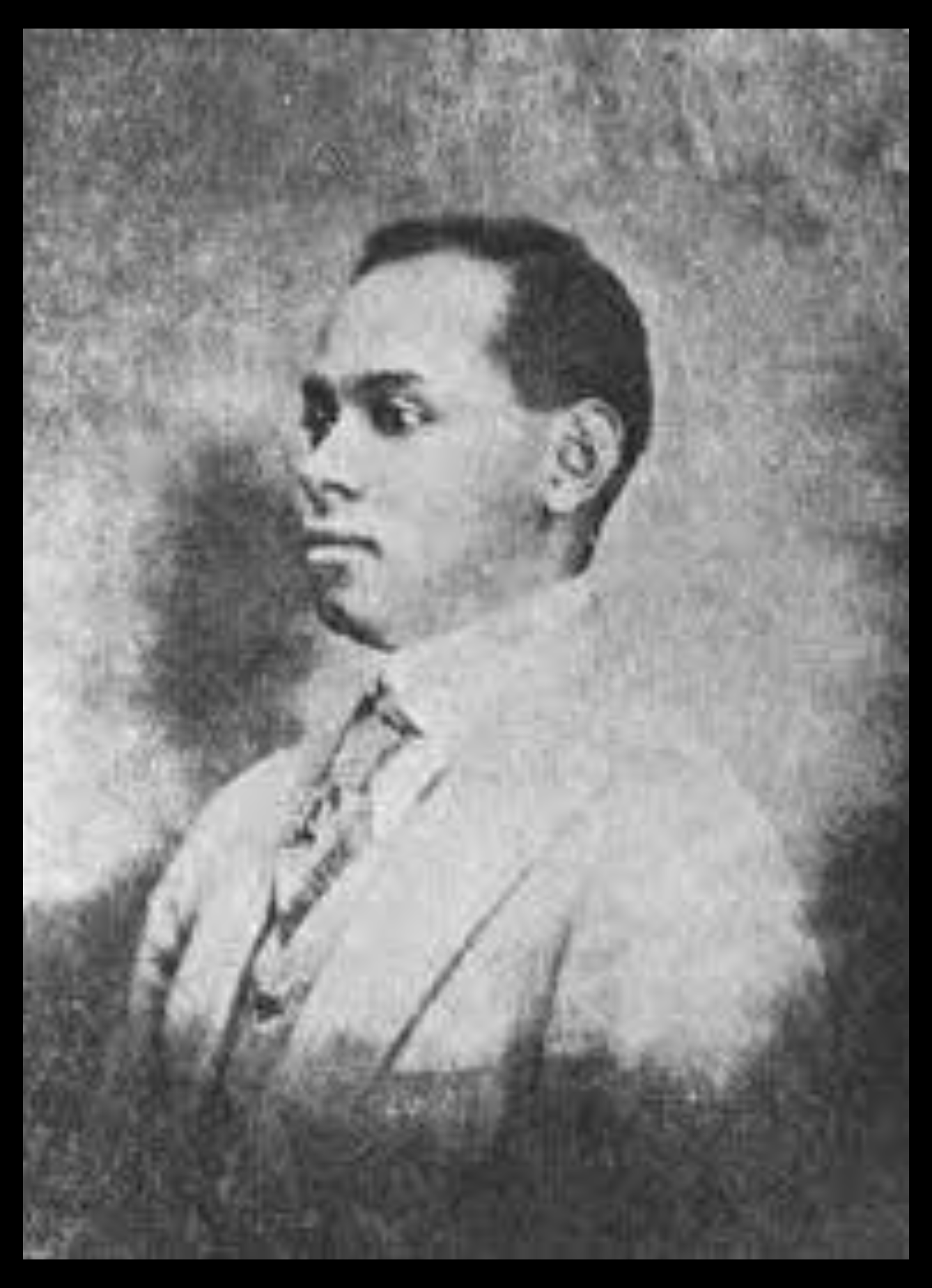

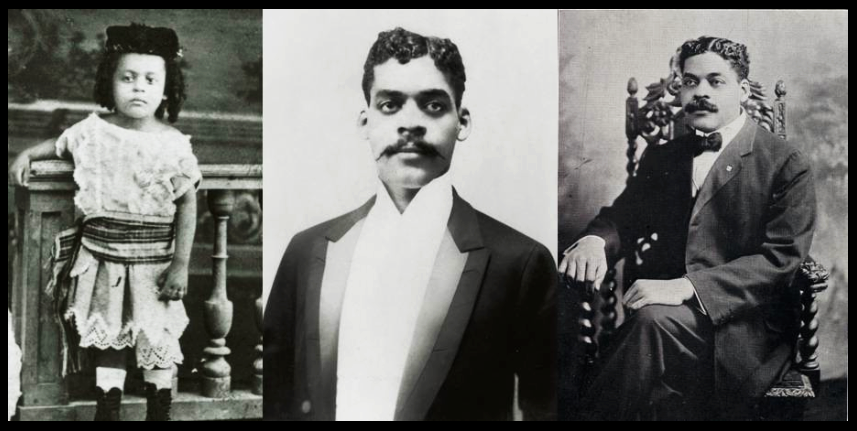

El erudito puertorriqueño negro Arturo Alfonso Schomburg dedicó toda su vida a compilar vastas colecciones de escritos que documentan eventos significativos en la historia negra. Antes de mudarse a la comunidad de Harlem en la ciudad de Nueva York, Schomburg fue miembro de los Comités Revolucionarios clandestinos de Puerto Rico, que organizaron el famoso levantamiento Grito de Lares de 1868, una revuelta que pedía la abolición de la esclavitud y la independencia de Puerto Rico. Schomburg eventualmente se convirtió en una figura prominente durante el Renacimiento de Harlem, que desafió las facetas ideológicas de la supremacía blanca a través de las artes literarias, visuales y escénicas.

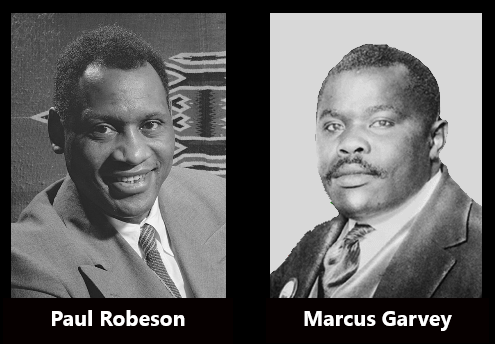

En muchas de sus actuaciones, el renombrado cantante, actor y comunista afroamericano Paul Robeson pedía a su audiencia un momento de silencio para expresar su solidaridad con el líder nacionalista revolucionario puertorriqueño encarcelado, el Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos.

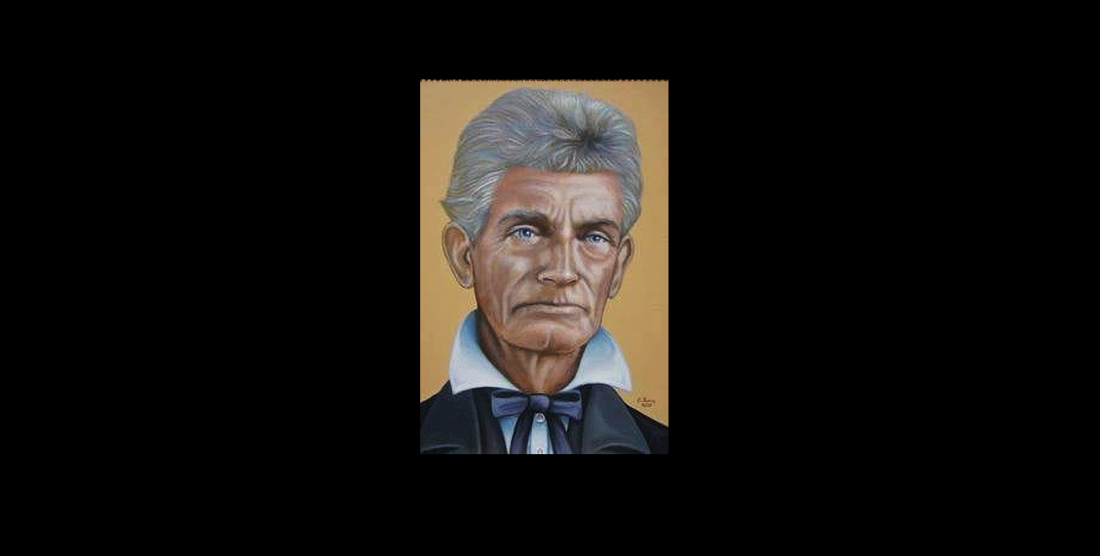

El joven Pedro Albizu Campos ganó reconocimiento entre las figuras afroamericanas por ser muy crítico con el racismo dentro de los Estados Unidos. La madre de Campos era negra, lo que le dio una idea de primera mano del impacto de la opresión racista. La franca oratoria de Campos contra las “prácticas racistas en la casa del imperio” llamó la atención del líder panafricanista Marcus Garvey, quien viajó a Puerto Rico para reunirse con el reconocido líder.

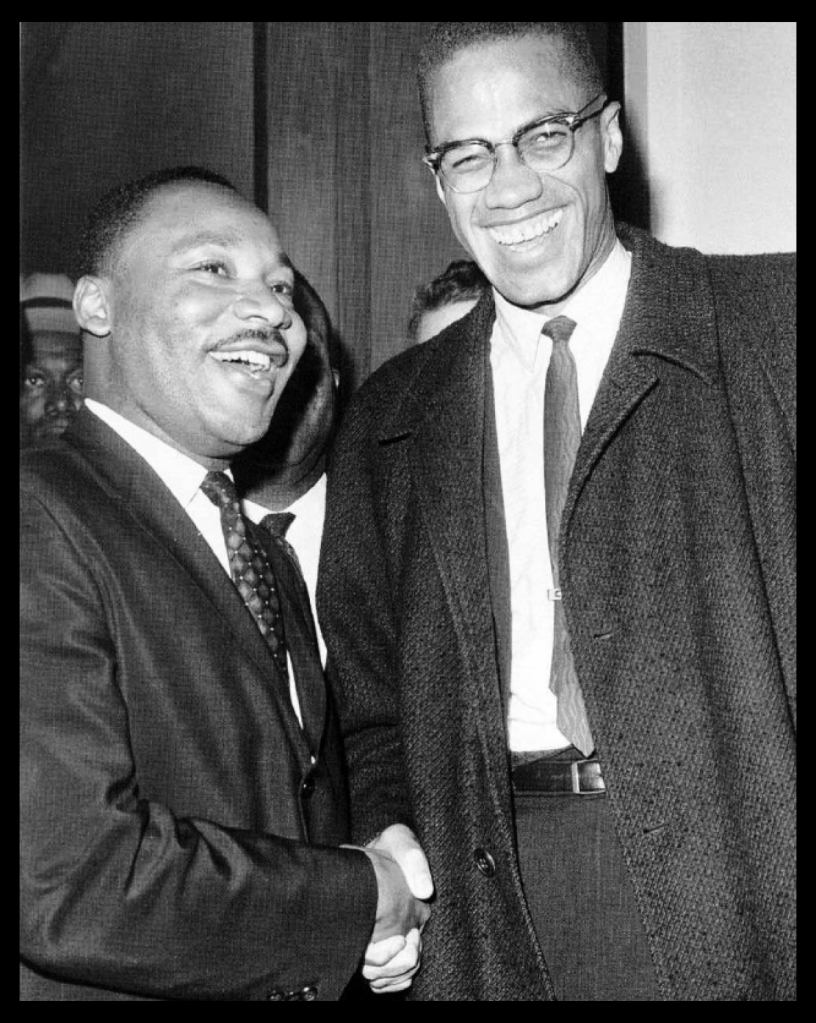

A pesar de sus diferencias en objetivos y tácticas, este encuentro fue muy simbólico para ese período de la historia. La Revolución Rusa animó las luchas de los trabajadores y los movimientos nacionalistas en todo el mundo, incluidos los Estados Unidos y Puerto Rico, e infundió un sentido de vulnerabilidad en la clase capitalista estadounidense.

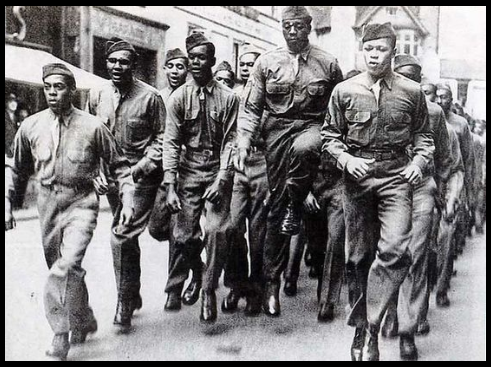

Lucha negra inspira militancia puertorriqueña

Los puertorriqueños han emigrado a la ciudad de Nueva York y los condados circundantes desde mediados del siglo XIX, en la mayoría de los casos, para escapar de la persecución colonial española. Pero en los años posteriores a la Segunda Guerra Mundial y hasta bien entrada la década de 1960, los puertorriqueños migraron a los centros industriales de EE. UU., a una tasa promedio anual de 63,000 debido a las dificultades económicas causadas por el colonialismo de EE. UU. en Puerto Rico.

Lo que encontraron los migrantes puertorriqueños no fue lo que esperaban cuando se desarraigaron en busca de una vida mejor. Además de la agonía de tener que venir a una tierra extraña, la experiencia puertorriqueña ahora incluía propietarios racistas codiciosos, discriminación laboral y de vivienda, estigmatización cultural por parte de los medios de comunicación, brutalidad policial y el terror de las pandillas blancas racistas.

Si bien los puertorriqueños comenzaron su éxodo a fine de la década de 1940, los afroamericanos ya estaban involucrados en su “Gran Migración” desde los estados del sur donde históricamente se habían concentrado. Huyendo de las leyes racistas de Jim Crow y del terror del Ku Klux Klan, más de 5 millones de afroamericanos emigraron al norte, noreste y California entre las décadas de 1920 y 1960.

El instinto de cualquier pueblo oprimido es buscar aliados y encontrar formas de resistir. Los puertorriqueños que enfrentaban las realidades del colonialismo y el empobrecimiento podían relacionarse con el movimiento de derechos civiles y se sintieron atraídos por su audacia.

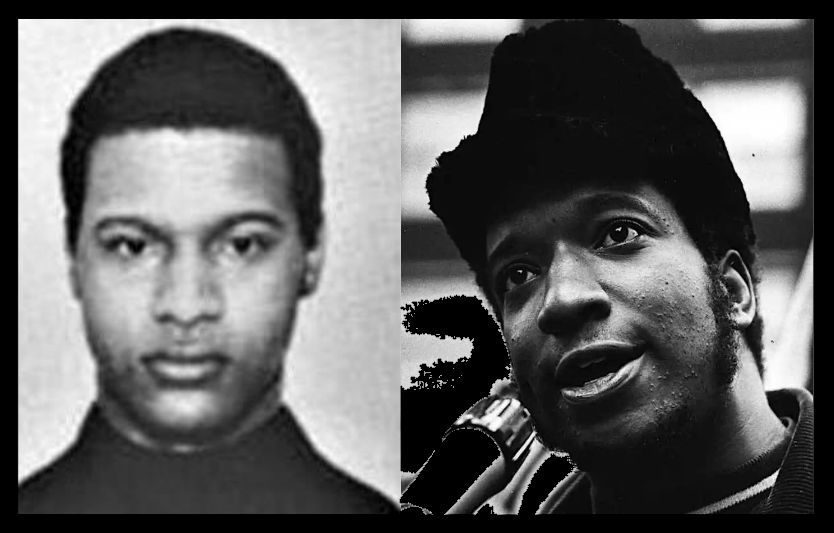

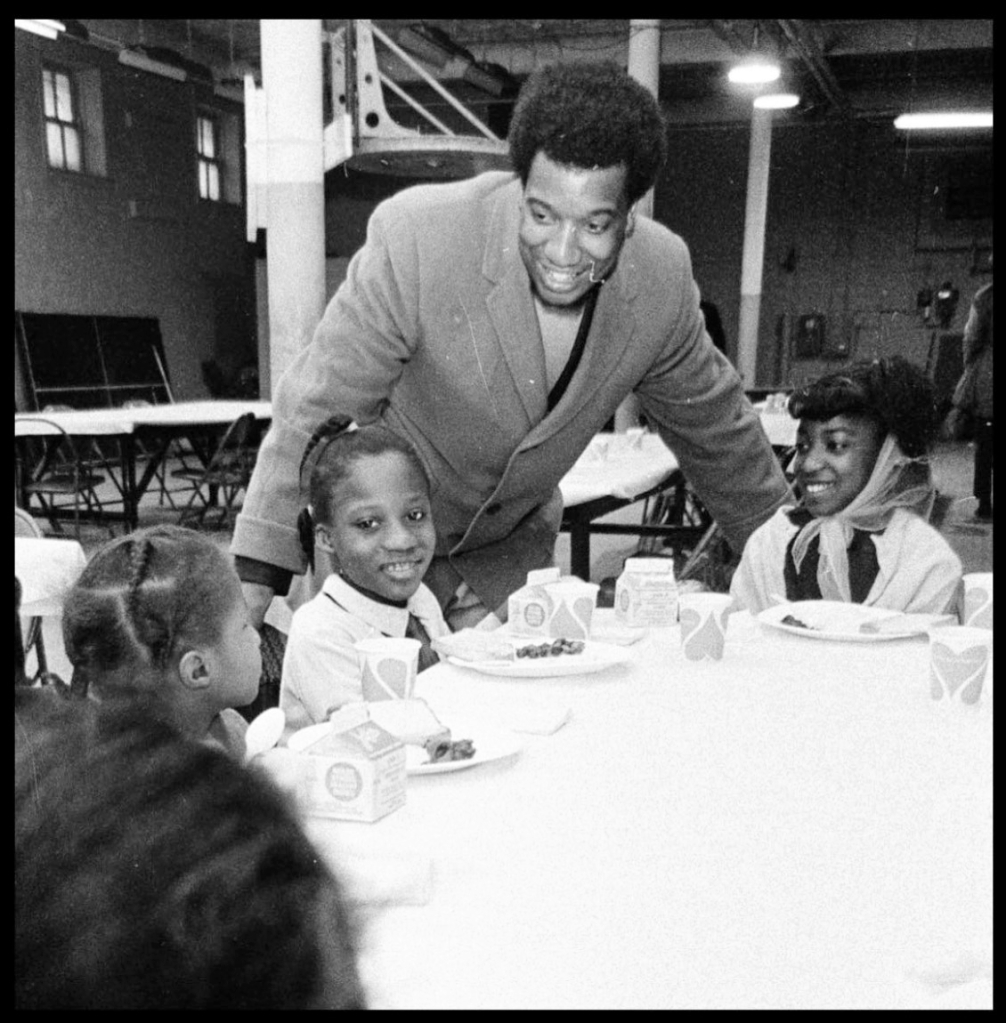

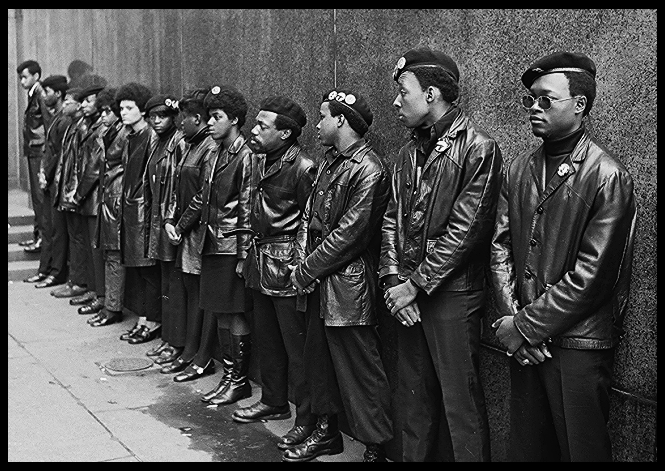

La Nación del Islam, integrada por afroamericanos de la religión islámica, comenzó a acercarse a los inmigrantes recién llegados con el objetivo de politizarlos. Y cuando el Partido Pantera Negra comenzó a organizarse en la comunidad puertorriqueña de Chicago, provocó la transformación de un grupo de jóvenes callejeros (“pandilla”) conocido como los Young Lords.

Los Young Lords fueron la primera organización revolucionaria puertorriqueña que surgió en los Estados Unidos a partir de las circunstancias políticas concretas de este país. Fueron un factor decisivo en la expansión de la militancia en las comunidades puertorriqueñas en varias ciudades de Estados Unidos. Al igual que los Panteras Negras, abogaron por una revolución multinacional en los Estados Unidos.

A medida que este movimiento ganaba impulso, los puertorriqueños adquirieron un sentido de esperanza y se sintieron inspirados para luchar por sus derechos políticos y económicos. Para la segunda mitad de la década de 1960, los puertorriqueños en los Estados Unidos se habían vuelto mucho más hábiles políticamente, gracias a las luchas de las masas afroamericanas.

Los afroamericanos y los puertorriqueños desarrollaron aún más su afinidad mutua basada en la resistencia a la opresión racista. En ciudades como Chicago, Filadelfia y Nueva York, en manifestaciones callejeras y en campus universitarios, las masas afroamericanas y puertorriqueñas se alinearon instintivamente entre sí en una lucha común. No era inusual que la bandera de liberación negra (roja, negra y verde) fuera acompañada por la bandera puertorriqueña.

Un ejemplo particularmente significativo de solidaridad, que se convirtió en una gran preocupación para la clase dominante, es la toma del City College en la ciudad de Nueva York por parte de los estudiantes en 1969. Los estudiantes afroamericanos y puertorriqueños captaron la atención de muchos en los EE. UU. cuando tomaron el control de los edificios del campus para exigir matrícula gratuita en el sistema universitario de la ciudad. Para demostrar aún más su audacia, estos estudiantes bajaron la bandera de los EE. UU. Del asta más alta e izaron la Bandera de la Liberación Negra y la Bandera de Puerto Rico. Era una imaginería de desafío y resistencia nunca antes vista en este país.

Las grandes lecciones aprendidas de esta experiencia siguen siendo profundamente relevantes hoy en día. La opresión negra fue fundamental en el surgimiento del capitalismo estadounidense, que los afroamericanos han enfrentado de frente en algunas de sus manifestaciones más opresivas. La lucha de liberación de las masas negras seguirá siendo una fuente de inspiración para todos los trabajadores y, en última instancia, será fundamental para forjar una unidad genuina.

¡VIVA LA SOLIDARIDAD NEGRA Y BORICUA!