By Carlos “Carlito” Rovira

Among the historical demands of the African American liberation struggle viewed with the utmost contempt by the capitalist class is the demand for reparations. At least 12 million Africans were kidnapped and taken to the Americas in the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

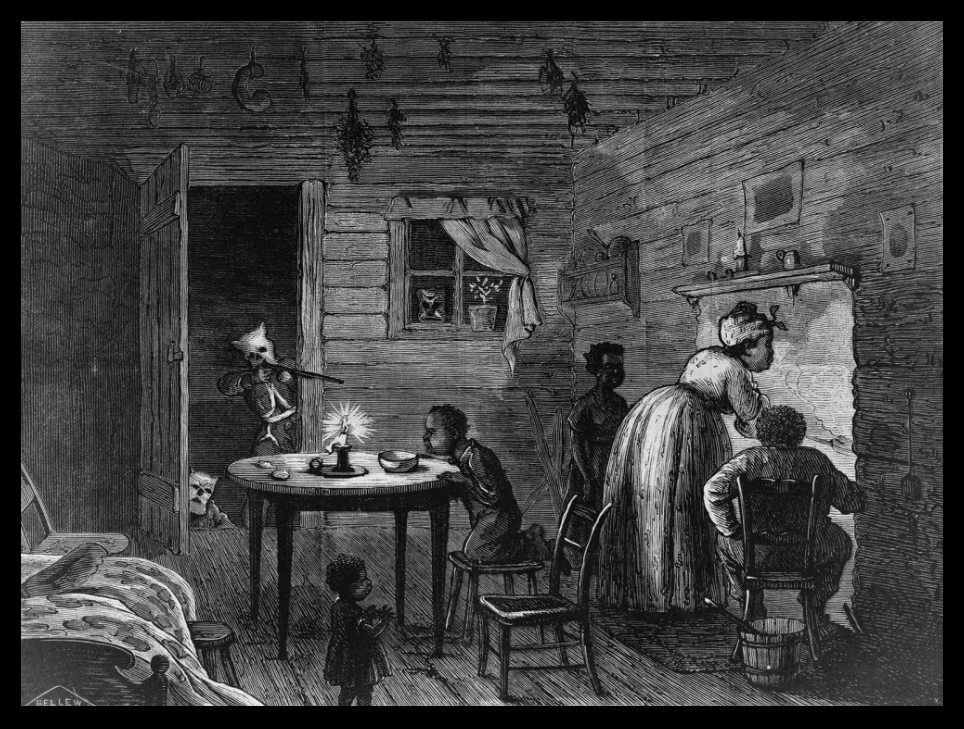

The demand for reparations is based on the outright theft, degradation and genocide of the African population during the hundreds of years of slavery in the United States. It is based on the continued impact of this period that lasts to this day in the form of systematic racism and inequality experienced by the Black community throughout the country.

It is also based on the continued benefits the U.S. capitalist class still derives from the wealth extracted from Black labor during the period of chattel slavery.

Unlike the human bondage of slavery in antiquity, African chattel slavery arose in the 15th century based on the expansion of capitalism. The exploitation of the labor of millions of African slaves allowed the then-infant European capitalist economies to achieve a level of growth never before seen by any social system.

Chattel slavery began around 1441 when armed Portuguese “explorers” captured Africans and shipped them to Europe. Once Christopher Columbus made his infamous intrusion into the Western Hemisphere, chattel slavery expanded and lasted well into the second half of the 19th century. This system formed the economic basis of deeply embedded racist ideology among people of European descent in the United States.

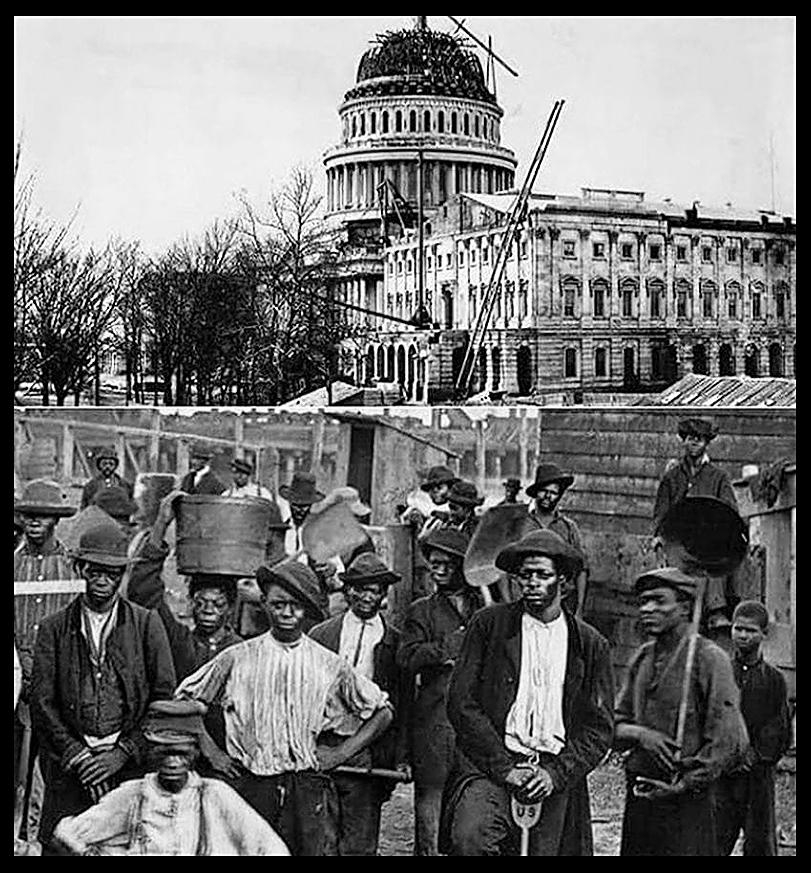

The initial process of rapid capital accumulation, a requirement for capitalist economic development, was accomplished by the European capitalist classes from the wealth created by enslaved Black labor and the massive theft of gold and other wealth from the Indigenous peoples of the Western Hemisphere also victims of genocide.

Today, bourgeois historians try to exonerate or distance the capitalist class from complicity in the brutal system of chattel slavery. But slavery, while not based on the “free” wage labor associated with capitalism, was inextricably bound to the development of this system. Slavery became an inseparable appendage of rising capitalism until its abolition in the 19th century.

The wealth accumulated from slave labor strengthened capitalist industries and commerce. Textile industries, agriculture and shipbuilding prospered as a result of cheaper goods and raw materials obtained by enslaved African labor. The more slavery expanded, the more it became an impetus for capitalist economic development not only in the United States, where slavery was strongest, but throughout the world.

But what was first a tremendous stimulant for capitalist economic growth ultimately became an economic depressant in the United States. The slave-based plantation economy in the South competed directly with the growing manufacturing economy in the north, based on “free labor.”

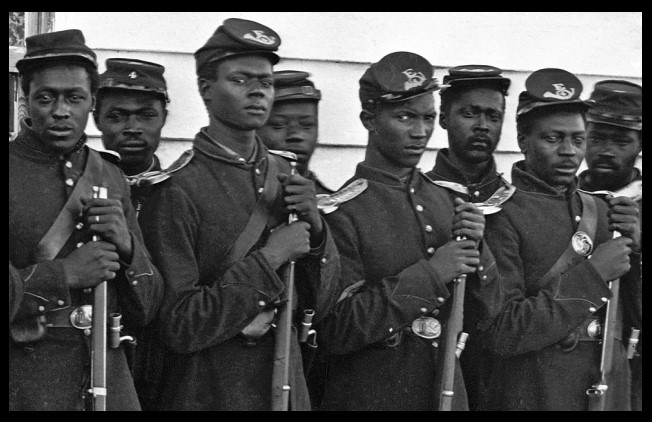

The competition between these social systems was the basis for the U.S. Civil War from 1861 to 1865. African chattel slavery in the United States was the most lucrative of all.

Chattel slavery was abolished after the Civil War, but the impact of that brutal system remained, both in the wealth of the U.S. ruling class and continued racist oppression of the Black population.

The colossal wealth today, amounting to trillions of dollars, is boasted about in stock market reports by the world’s richest corporations like FleetBoston Financial, the railroad firm CSX and the Aetna insurance company. These entities owe their growth to the brutally exploited labor of millions of African people.

But like any system of exploitation, slavery also provoked the aspirations of the Black masses for justice and compensation. The demand for reparations is an expression of these aspirations to benefit from the vast wealth that millions of enslaved people produced.

The exact formulation of the demand for reparations has varied over the many phases of the Black liberation struggle through the era of slavery itself, the period of Reconstruction following the Civil War, to the present day. But whatever the form in which the demand has manifested, it has always expressed the collective desire of African Americans to be compensated for the criminal exploitation they endured as an enslaved people.

`Forty acres and a mule’

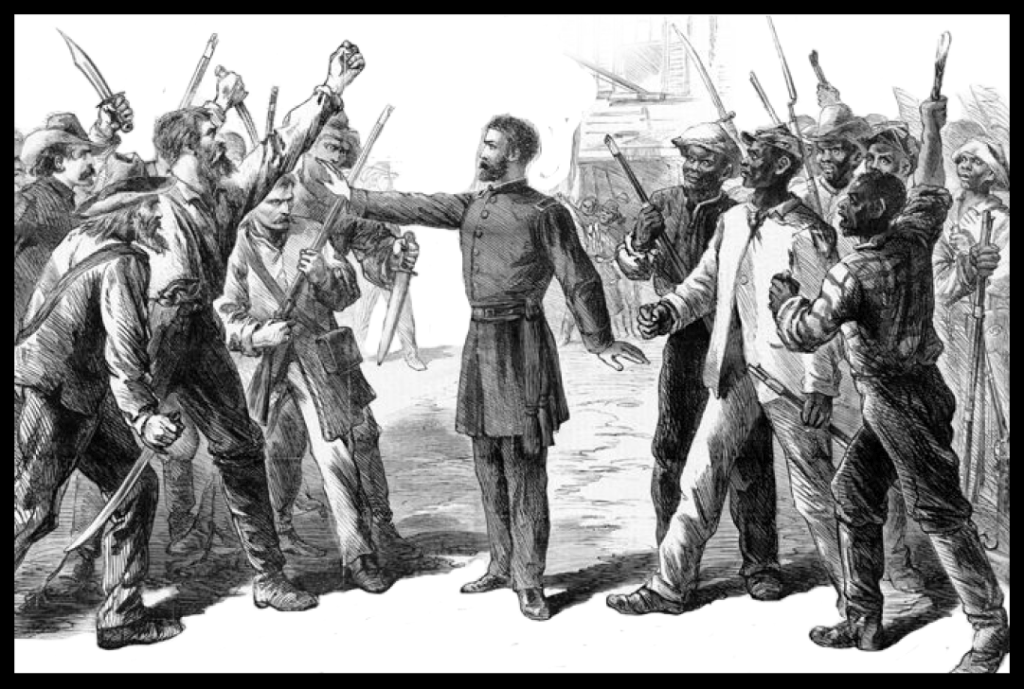

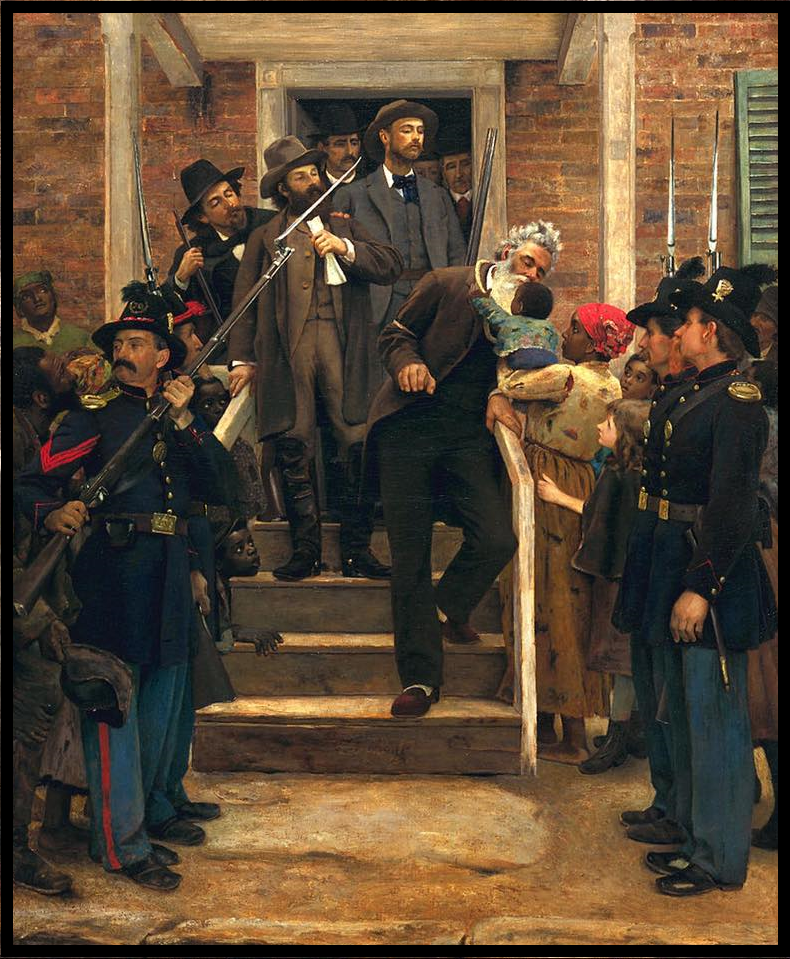

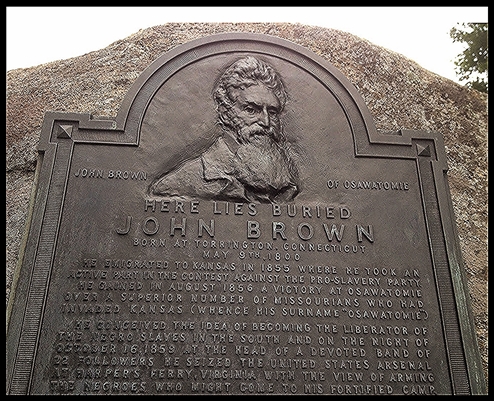

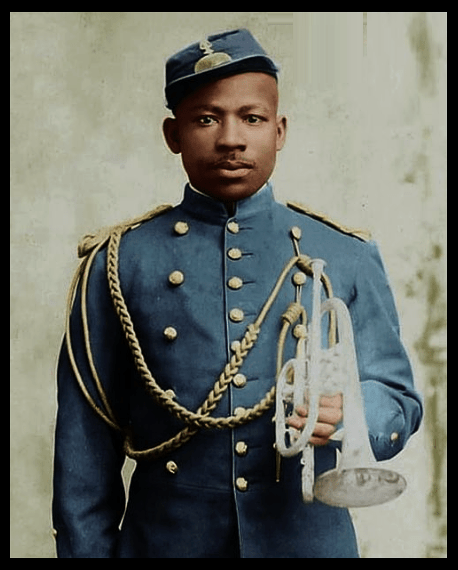

During the Civil War, the southern slave-owning class held a special hatred for the northern general William Tecumseh Sherman. In 1864 and 1865, Sherman led an army of Black and white Union soldiers marching through South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. Along the way, he ordered the total destruction of munitions factories, crops, railroad yards, clothing mills, warehouses and other targets to deny resources to the Confederacy. It was an effective measure of psychological warfare aimed at all who resisted the will of the Union Army.

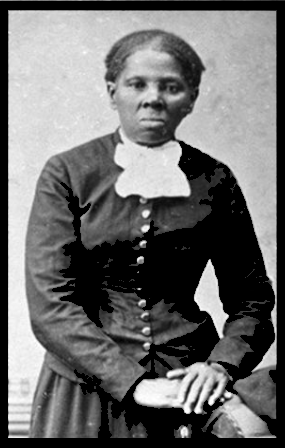

On Jan. 11, 1865, Sherman met with leaders of the Black community in Savannah, Georgia. Most of them were former slaves. The spokesperson of the Black leaders was 67-year-old Garrison Frazier, who was born a slave in North Carolina.

Frazier gave voice to the aspirations of the millions of African Americans who had just been released from slavery as a result of the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation. “The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land,” Frazier told the Union general.

These African Americans were a principal factor in Sherman’s decision to issue Special Field Order 15 on Jan. 15, 1865. That military order provided 40,000 former slaves with 400,000 acres of land confiscated from the defeated slave owners. It is believed to have been the origin of the demand for “40 acres and a mule.

For the first time, a representative of the northern capitalist class had recognized, in a limited way, the rights of former slaves to receive some form of compensation for their centuries of oppression. And while the order was issued for tactical purposes by the northern capitalist government in its campaign against the southern slavocracy, it provided a glimpse of what the oppressed Black nation could achieve in a full-blown social revolution.

Reversal of Civil War gains

Hopes for real economic reparations for former slaves were short-lived. The immediate needs of the northern ruling class in crushing their southern competitors were replaced by the overall goal of stifling the aspirations of the oppressed Black masses. Sherman himself went on to unleash U.S. government terror against the Native American people.

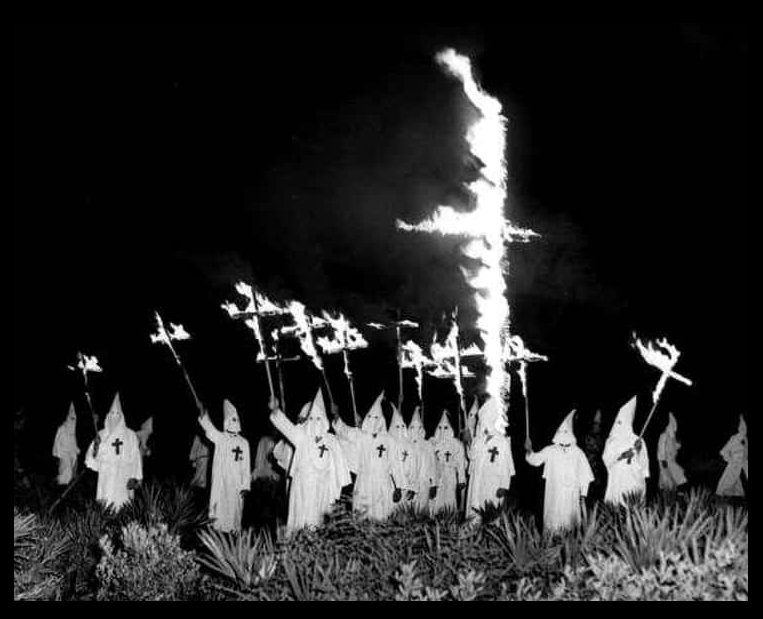

The overthrown slave owners were enlisted as allies in this project. Former members of the Confederacy engaged in counter-revolutionary activities, setting up the terrorist Ku Klux Klan to roll back the gains of the postwar period of Radical Reconstruction.

One of Andrew Johnson’s first acts as president after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln was to rescind Special Field Order 15, returning the old land titles to their former owners. Throughout Johnson’s presidency, he vetoed every proposal that granted land to former slaves in the southern states and the western frontier.

Radical Republicans made other attempts to pass legislation compensating former slaves, such as providing pensions for the former slaves. These bills met fierce opposition in Congress; none survived.

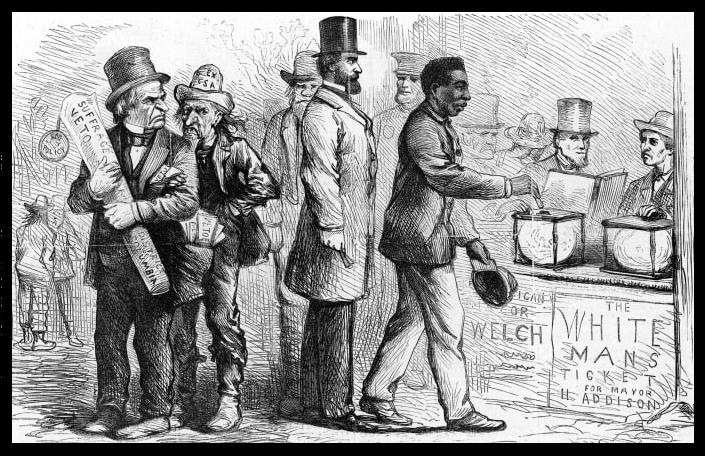

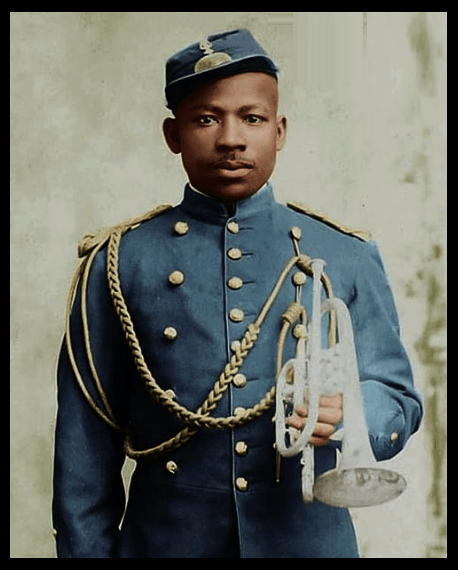

As the United States entered the 20th century as a rising imperialist power, it became ever clearer that the capitalist class motives during the Civil War had nothing to do with genuine Black emancipation. Instead of receiving reparations, African Americans were the constant target of disenfranchisement, persecution and racist terror.

The struggle to win reparations for African Americans diminished in the earlier part of the 20th century, largely overshadowed by the necessary struggles against lynching and KKK terror. At the height of the Civil Rights movement during the 1950s and 60s, reparations once again became a central demand of the Black liberation struggle.

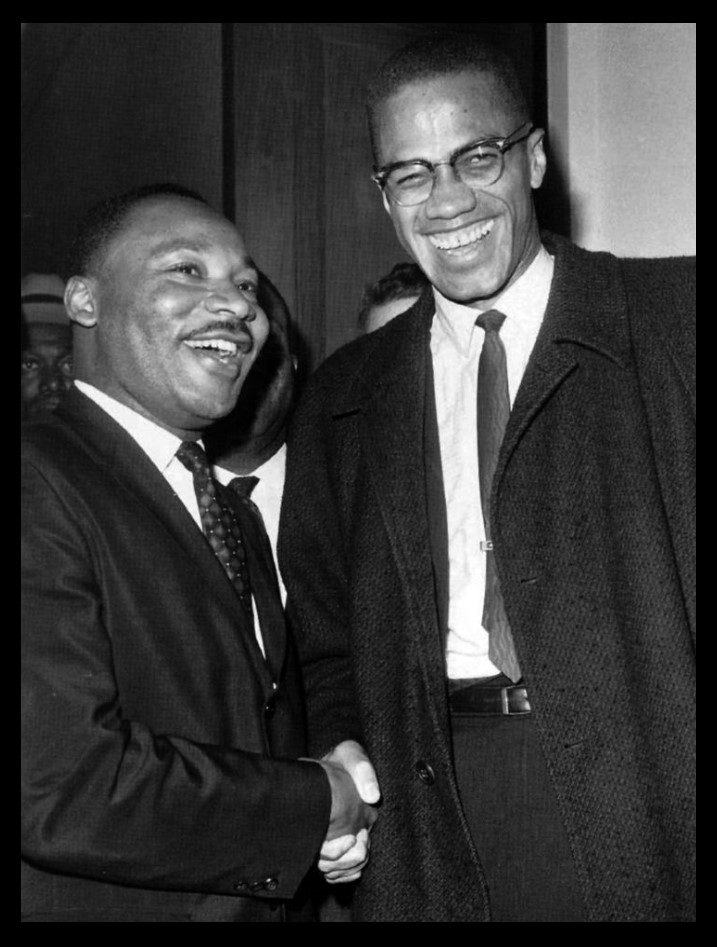

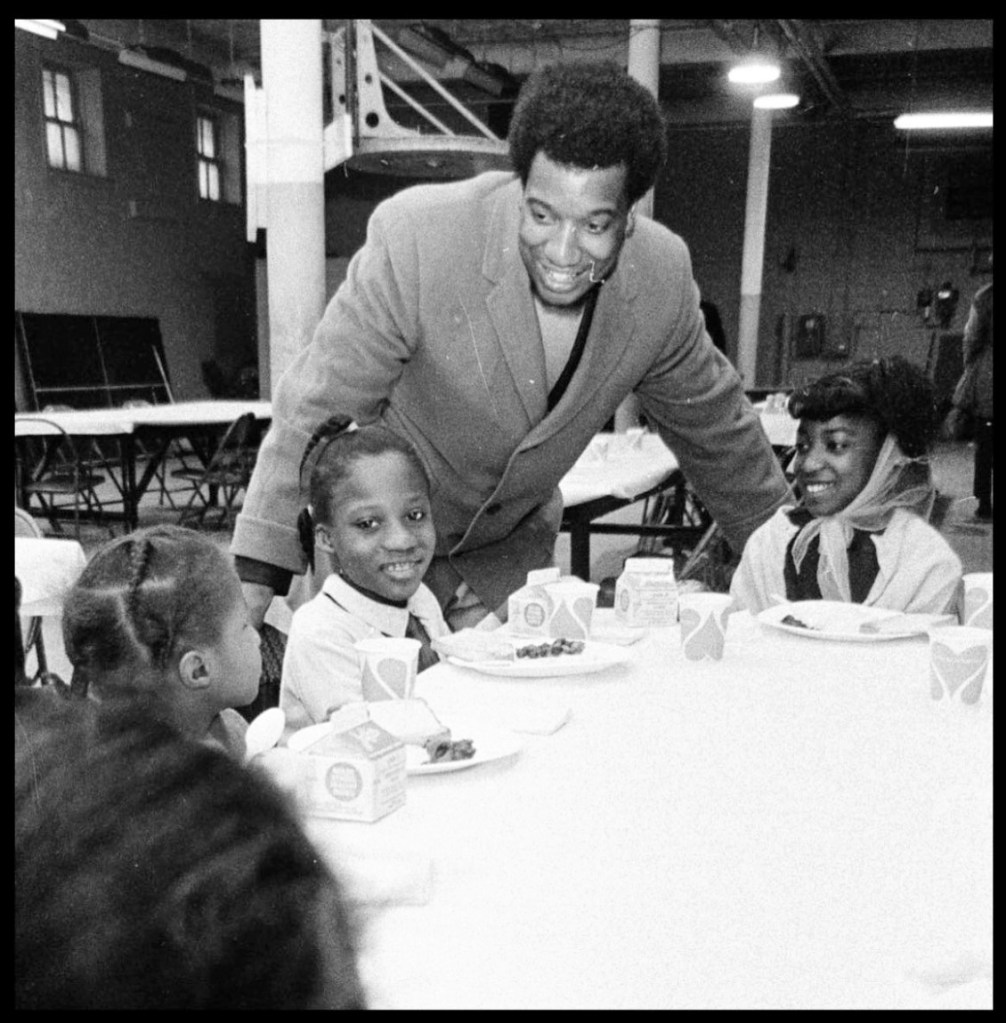

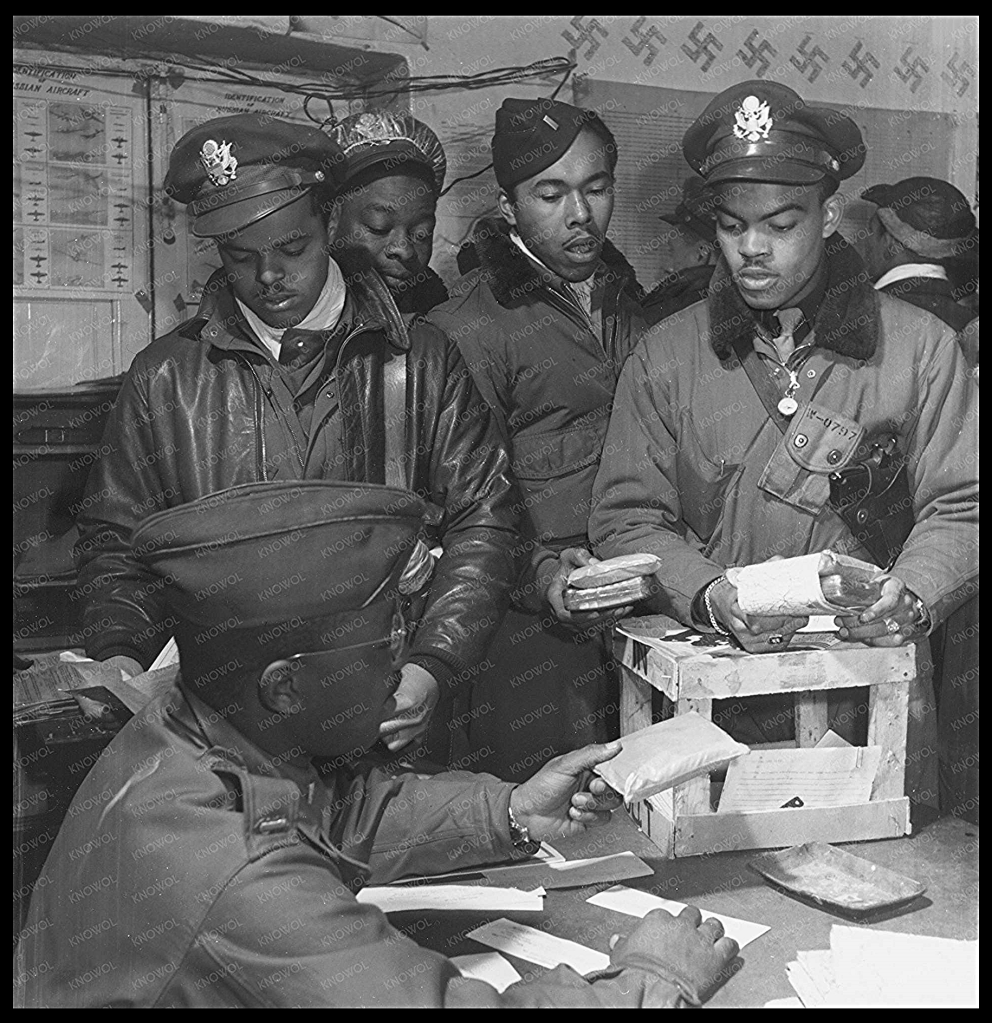

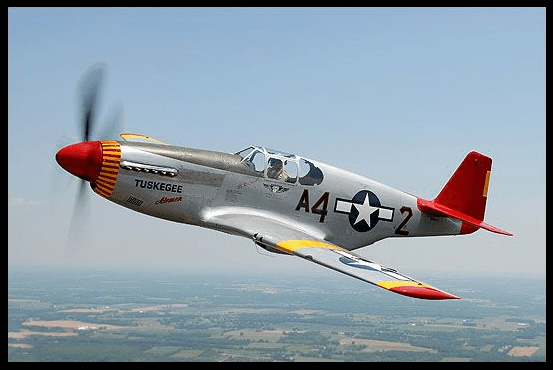

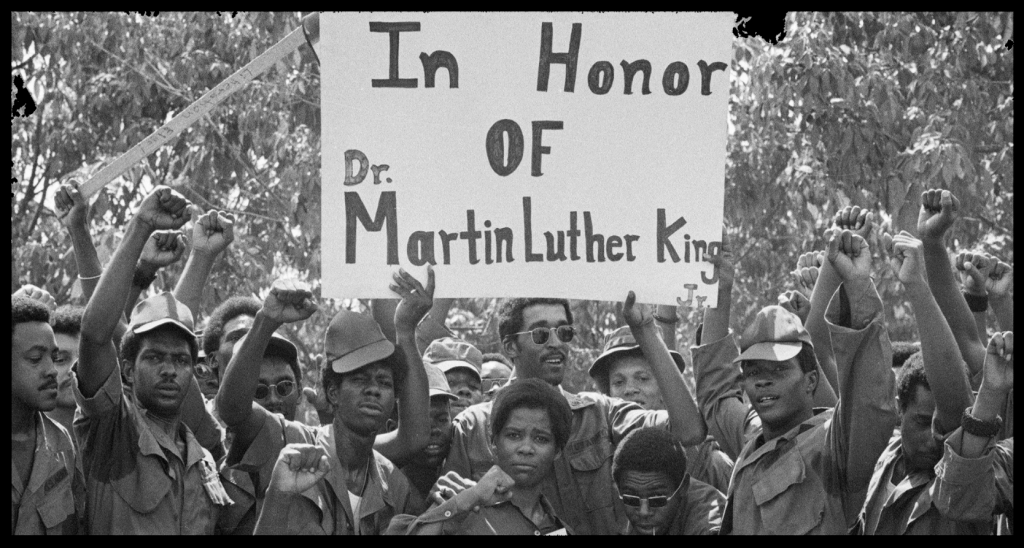

Prominent figures like Queen Mother Moore, the Black Panther Party, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Nation of Islam and others reintroduced the demand for reparations, often in militant and defiant ways.

The complicity of white people in Black oppression can only be rectified when they raise the banner of Black liberation as their very own.

During the course of the mass civil rights and Black liberation movements, the U.S. government was forced to allow some progressive legislation. In particular, voting rights, expanded welfare programs and some elements of affirmative action were achieved although all of them are under constant attack.

The question of property rights

But throughout this period, all sectors of the U.S. ruling class have been hostile to any form of reparations to the African American community. The reason is simple: The demand raises the question of property rights. The bottom-line function of the U.S. government is to preserve capitalist property against all demands from those without property.

Economics is the lifeblood that allows for human social development. Destroying, hindering or depriving a people of an economic means of life is an essential step for an oppressor in carrying out the business of subjugation. This is why the capitalist class is hostile toward any reference to reparations.

Of course, the capitalist rulers never hesitate to demand reparations in the form of financial compensation when it comes to their own property or interests. For example, they still whine about U.S. capitalist property that was expropriated by the 1959 Cuban Revolution.

Ruling-class commentators and pundits try to use bourgeois legality in arguing that African slaves are no longer living and that the claim for reparations should not apply to their descendants. But the wealth created by slave labor became the foundation of many U.S. corporations and was the basis for the rise of the U.S. capitalist class: the railroad conglomerate CSX, Aetna, JP Morgan Chase, WestPoint Stevens, Union Pacific and Brown University, to name just a few.

It is by that bourgeois legality that the wealth created by enslaved people and appropriated by the slave owners has continued in the form of corporate wealth and passed down through inheritance laws to families and individuals.

Under the legal codes of capitalism, the debt owed to the ancestors of the vast majority of African Americans today should be recognized by the same inheritance laws by which the rich have benefited. The denial of these rights is another example of the racist disenfranchisement of the Black nation in the United States.

What will reparations look like?

Of course, the concrete expression of how reparations should be granted has generated discussion and debate, even among advocates of reparations. For example, some call for reparations in the form of material incentives such as funds for education programs.

At a September 2000 forum sponsored by the Congressional Black Caucus and initiated by Rep. John Conyers, Congressperson Tony Hall supported a call for a panel to study the call for reparations. “I would hope that it would consider among many things, investments in human capital for scholarships, for a museum like Congressman [John] Lewis has proposed, for things that would improve the future of slaves’ descendants,” he testified.

The Black Panther Party placed reparations at the center of their political perspective. Hall, who is white, articulated a modest message. He had sponsored legislation calling on Congress to issue a formal apology for slavery something that the U.S. government has never done. The version of reparations he described is one designed to be tolerated by some sector of the capitalist class itself.

Activist and author Sam Anderson, representing the Black Radical Congress at the same 2000 panel, projected a more radical vision of the movement for reparations. “[A] comprehensive reparations campaign embraces all of our sites of struggle and areas of concerns,” he said. Anderson laid out a program of fighting for free health care, debt cancellation both for the Black community in the United States as well as African nations and freedom for political prisoners. “A reparations campaign is fundamentally anti-racist, anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist,” he said.

Reparations and Socialism

Throughout the decades that the demand for reparations has been raised, it is clear that the ruling class is vehemently opposed to any form of economic redress for the descendants of victims of slavery. Every effort to make the most moderate version of reparations is rejected out of hand.

Every effort of groups like the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America and others deserves the support of all working people of every nationality. Solidarity among the working class means recognizing the right of oppressed nations to real redress for the exploitation of centuries.

Reparations for African Americans automatically means the expropriation of the capitalist class. In short, taking back the wealth, and everything connected to it, that the rulers stole from oppressed and exploited people since their existence first began.

Socialists and revolutionaries concern themselves with raising the anti-capitalist essence of the demand for reparations, making it a central theme for the revolution in this country. For anyone to claim that they are “socialist” but are either ambiguous or opposed to reparations are in essence promoting a sham version of “socialism.”

Given the dynamics of the class struggle in the United States and the extreme reliance on racism by the ruling class, reparations for the oppressed automatically imply the expropriation of the capitalist class.

The demand for African American reparations has wide-ranging implications with regard to the history and social structure that prevails in this society.

It is a demand that has been taken up around the world by other oppressed nationalities. In fact, reparations for Indigenous-First Nation people after the U.S. genocidal campaign, for Mexican people for the conquest of territory, for the Puerto Rican people, for more than a century of U.S. colonialism, for Cuba, Palestine, Haiti, Venezuela and so on. These and more are part and parcel of the U.S. working-class program for socialist revolution.

REPARATIONS FOR AFRICAN AMERICANS, AFRICA & THE AFRICAN DIASPORA, NOW!